As we have seen previously (see the White Paper “Wealth and Mobility”), there is a steady, long-term relationship between per-capita wealth and per capita miles of automobile travel. Increasing auto-mobility fosters wealth, primarily through enhanced labor productivity.

Now, however, this virtuous cycle is threatened by the steady growth in traffic congestion, especially during the last two decades. In order to better understand what causes this growing gridlock, we can examine some of the growth trends that relate to transportation. For this purpose we will focus on trends in the San Francisco Bay area; however, what is true for the Bay area turns out be representative of circumstances in most other large metropolitan areas, both in the United States as well as in other developed economies.

Case 1: the San Francisco Bay Area

As a prerequisite to distributing any transportation funding to the states, the federal government requires that each transportation region establish a Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) that will coordinate local planning and financing to ensure optimal use of federal and local transport dollars. In the San Fransisco Bay Area the MPO is the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC). This organization is responsible for coordinating investments in transportation for the seven million people residing in the nine counties comprising the region. Their transportation forecast for the coming decades is sobering.

Over the 30 years ending in 2030 the MTC expect the population to grow about 30%, jobs will grow nearly 40%, and vehicle miles of travel book grow over 40 percent. In the meantime, they forecast growth in roads construction of only 5%.

When you consider the traffic in 2000 at the peak of the dot-com bubble, it is not difficult to imagine what the future will look like when you pour 30% more people driving over 40% more miles

each year on to a roadway system that is only 5% bigger: this is a formula for gridlock on a huge scale.

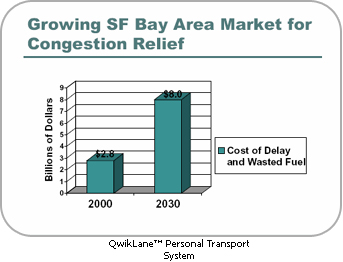

In fact, the planners at the MTC have given us some numbers that begin to quantify the scope of this coming gridlock. They note that in 2000, Bay area drivers lost over 350,000 hours each day due to traffic congestion. Based on the growth trends provided above, they forecast that the impact of traffic delay will grow to nearly 1 million hours daily in 2030. That amounts to a stunning congestion tax on Bay area commuters. Indeed, when you account for the value of this wasted time and also add the cost of the wasted fuel that is consumed in congested traffic, the annual cost of gridlock in the Bay area is forecast to grow from $2.8 billion in 2002 to a staggering $8 billion in 2030.

Why don't we just build more roads? Two trends conspire to make this solution increasingly difficult. First, highway construction costs, especially in those locations where congestion is most acute, are rising sharply. Second, this trend is aggravated by the fact that the sources of funding that are available to create our highway infrastructure are shrinking.

First, consider the cost side of the equation. In 2006 new highway infrastructure in an urban area typically costs $7 million to $10 million per lane mile. However, in those areas where we find the worst traffic there is usually little or no room to build additional lanes. Often the highways are at their full capacity. Further widening would require rebuilding overpasses and moving sound barriers deeper into the backyards of property owners; or, additional capacity would have to be built above existing roadway. Either of these solutions raises the cost of construction exorbitantly.

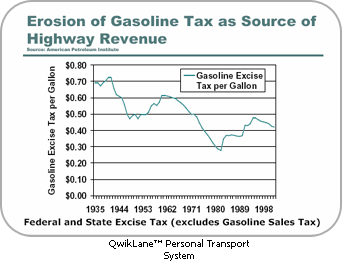

Revenue for highway maintenance and expansion is also a problem. Growing claims for taxpayer funds make it more and more difficult to allocate additional money for highway infrastructure. In fact, it is widely agreed that there is a massive backlog of needed repairs for the existing highway, bridge and tunnel infrastructure. Add to this funding squeeze the fact that the primary source of highway capital, state and federal gasoline excise taxes, has been shrinking in real dollar terms for many decades. Two factors are at work here. First, the tax rates are fixed; therefore, as prices rise with inflation the real value of these tax dollars decreases in constant terms. And, it is very difficult for politicians to muster the support for raising the tax rates from current levels. This can be seen clearly in the graph below. The long term trend reveals a steady decline in revenue per gallon, punctuated infrequently by sharp increases when the government succeeds in pushing through a tax rate increase. Had these taxes been tied to the price, like the sales tax, revenues would have kept up reasonably with inflation.

Second, the dramatic increase in average fuel economy over the last several decades results in fewer gallons of gas purchased for the same number of miles driven; this in turn results in reduced gas tax collections per mile of highway travel. Finally, politicians have raided the highway trust funds for use on other projects. Taken together, the result is not only an under-investment in highway infrastructure, but a failure to even keep up with maintenance of the existing system.

What does all this mean for the future? We have seen that the highway expansion begun in the 1960’s fostered an increasing per-capita use of automobiles, as expressed in vehicle miles of travel, which in turn lead to a consistent per-capita growth in GNP during the last seven decades in the United States. Now however, if the planners are right, this benevolent effect may be in the process of reversing itself. Our mobility decreases with traffic congestion. As a result our access to jobs, schools, health care, shopping and entertainment are diminished. Businesses will encounter a shrinking labor pool and reduced ability to manage inventories, deliveries and other economic decisions for maximum efficiency. Taken together, these effects of gridlock will act as a strong drag on future economic growth to the detriment of everyone.

It doesn't have to be this way. The ever-growing popularity of the automobile after World War II quickly lead to urban traffic congestion that was severe in many areas. In the 1950's and 60's this condition was largely alleviated through the creation of the federal interstate highway system. The return of gridlock today – unwelcome as it may be – is a continuing reflection of the success of auto-mobility in enhancing our economic wellbeing. Just as the interstate highway system provided a leap in capacity and efficiency by means of transportation innovation in the middle of the 20th-century, today we need to look once again to innovation to find a solution for current traffic woes. Automating the driving function for a significant portion of the vehicles on the highway today would provide a leap in throughput, efficiency and safety even greater than that provided by the interstate highway system. The required technology is already available, the cost is affordable and can be paid by the users who directly reap the benefit. These users will pay because the benefit substantially exceeds the cost. Because the users will bear the cost, including the return on invested capital, an automated highway system could be built entirely with private funding.

“Smart Growth” Will Not Relieve Highway Needs

Urban planners seem to be of two minds when it comes to the looming traffic crisis. On one hand, their planning actions are in line with the proponents of “Smart Growth”. This school of planning holds that future development should focus on mixed-use projects; the goal is for residents to live in close proximity to jobs, schools, shopping and entertainment. This is a plan based on hope, hope that such an inclusive architecture will result in less driving. Bonus points awarded if the development is concentrated near significant transit stops or hubs.

On the other hand, these same planners are coldly realistic, perhaps fatalistic, when it comes to their forecasts of future VMT and congestion trends. Despite promoting and implementing programs and regulations that support these Smart Growth ideals, they don’t seem to expect them to make much of a dent in our travel patterns and trends.

It is not difficult to understand why the Smart Growth hope flies in the face of reality. Suppose you move into one of these new neighborhoods and your job happens to be located in the project. Who wouldn’t love that? And there would be one less commuter on the roads. Suppose further the boutique restaurants nearby offers great food for a

reasonable price. And the convenience store is, well, convenient. Your spouse works somewhere else, but nothing’s perfect…

Presumably to the extent this picture is true for a large percentage of the inhabitants, how much reduction in VMT can one reasonably expect? 50%? Even if this were true, and all future property development were along the lines of the New Urbanist concepts, this would only accommodate half of the anticipated growth in VMT, leaving enough traffic to overwhelm the road infrastructure.

|

|